Event location: Room 401, Arts and Social Sciences Building, Stellenbosch University

Event date and time: 30/08/2018 13:00:00

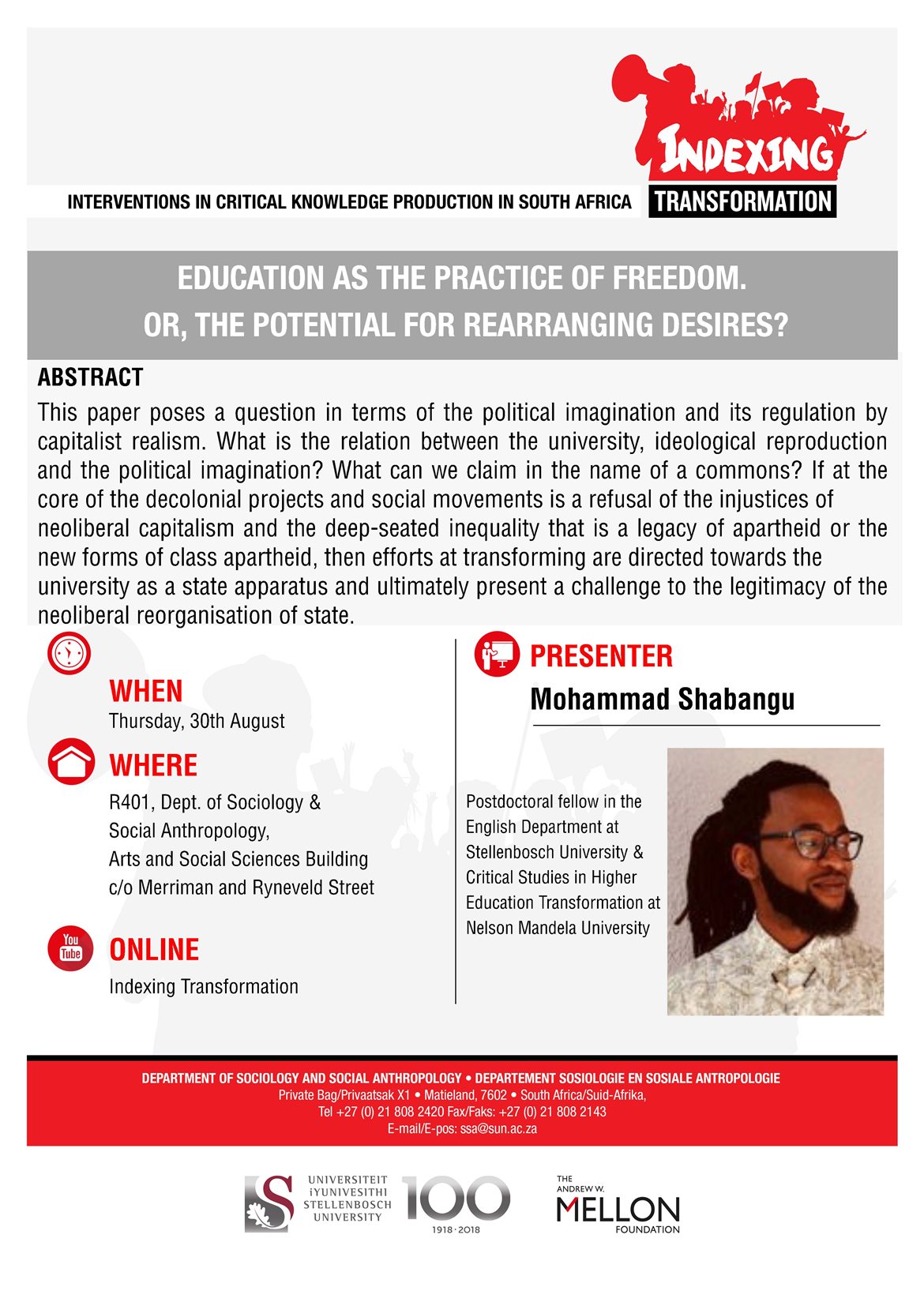

This paper poses a question in terms of the political imagination and its regulation by capitalist realism. What is the relation between the university, ideological reproduction and the political imagination? What can we claim in the name of a commons?

If at the core of the decolonial projects and social movements is a refusal of the injustices of neoliberal capitalism and the deep-seated inequality that is a legacy of apartheid or the new forms of class apartheid, then efforts at transforming are directed towards the university as a state apparatus and ultimately present a challenge to the legitimacy of the neoliberal reorganisation of state.

I am interested the nature of State that is being contested, but also the state of mind, where the word state implies a mental or emotional condition. Thinking with Lauren Berlant’s work on cruel optimistic relations, I speculate on the South African university’s shared ideological complicities. I argue against its emphasis on the production of a subject that is in synch with the reproduction of capital, and well-suited for insertion into its structures. This is evidence of the role universities plays in sustaining the enduring fantasy of ‘the good life’. Therefore, a mode of inquiry that asks questions about the affective registers of the present enables us to assess the ways we keep returning to the scene of a fantasy of the good life in our individual or collective imaginer. To invest optimism in an object it is to project that investment towards the future, to say with all good conscience that better days lie ahead. But structural inequalities and social insecurities indicate that it matters little what one feel about the ROI of one’s faith, better days can feel distant, and we might be left feeling disappointed, neither upward nor mobile, in fact we may even feel ourselves confined to a life of attrition in which we carry around the excess baggage and hard materiality of the quotidian. And yet here we are optimistically living on even when that optimism feels like depression, anger, dissent or protest. What magnetizes the university’s desire and fidelity to a certain mode of production, even when that mode proves painfully unsustainable?